Tokyo Drifter (1966) Film Review and Summary

STRONG 6/10

The concept of mise en scéne within film is a polarizing one. In essence, the classification relates to anything that a film is composed of; the tangible and intangible aspects. Whether it’s cinematography, set design or narrative storytelling, mise en scéne is a broad umbrella when attached to a film. While I am unfamiliar with many of director Seijun Suzuki’s other films, I have the understanding that he is known for his usage of this term as a way to either excuse or explain the avant-garde, if not incomprehensible, spiraling narratives that he depicts. Tokyo Drifter certainly reinforces this notion for good and bad.

The plot that Tokyo Drifter follows is a simple one. A Yakuza boss decides to disband his gang, Tetsuya (Tetsuya Watari) is one of his loyal enforcers that finds little fulfillment in a life outside of crime and violence. A rival gang leader, Otsuka (Hideaki Esumi), looks to take advantage of this apparent vulnerability to usurp real estate and property by force, but sees Tetsuya as a threat to these endeavors. After confrontations between the two, Tetsuya determines he must always be on the run to protect himself, but Otsuka sends a hit-man, Tatsuzo (Tamio Kawaji), to neutralize the protagonist. After numerous escapes, Tetsuya believes he is finally safe, but he is appalled to find out that his former boss, Kurata (Ryūji Kita), wants him dead as well to prevent further complications. Tetsuya returns home to avenge himself, but all of the betrayal he has endured has made him disillusioned and committed to a lifestyle of isolation.

The overarching theme is bluntly said by Tetsuya in a scene where we finally receive some character development in relation to his priorities. Testuya exclaims that he “can’t be around someone who has no sense of duty”, a sentiment which abundantly presents itself throughout the film by means of his composure. Tetsuya vows a life of loneliness, but he still understands when it is time to make his presence known again. Such as the film’s final sequence where he returns and saves his lover, Chiharu (Chieko Matsubara), but still remains dedicated to his wandering life of independence. The brutality of his occupation doesn’t disgust Tetsuya, what revolts him is the lack of morality that many of his peers demonstrate.

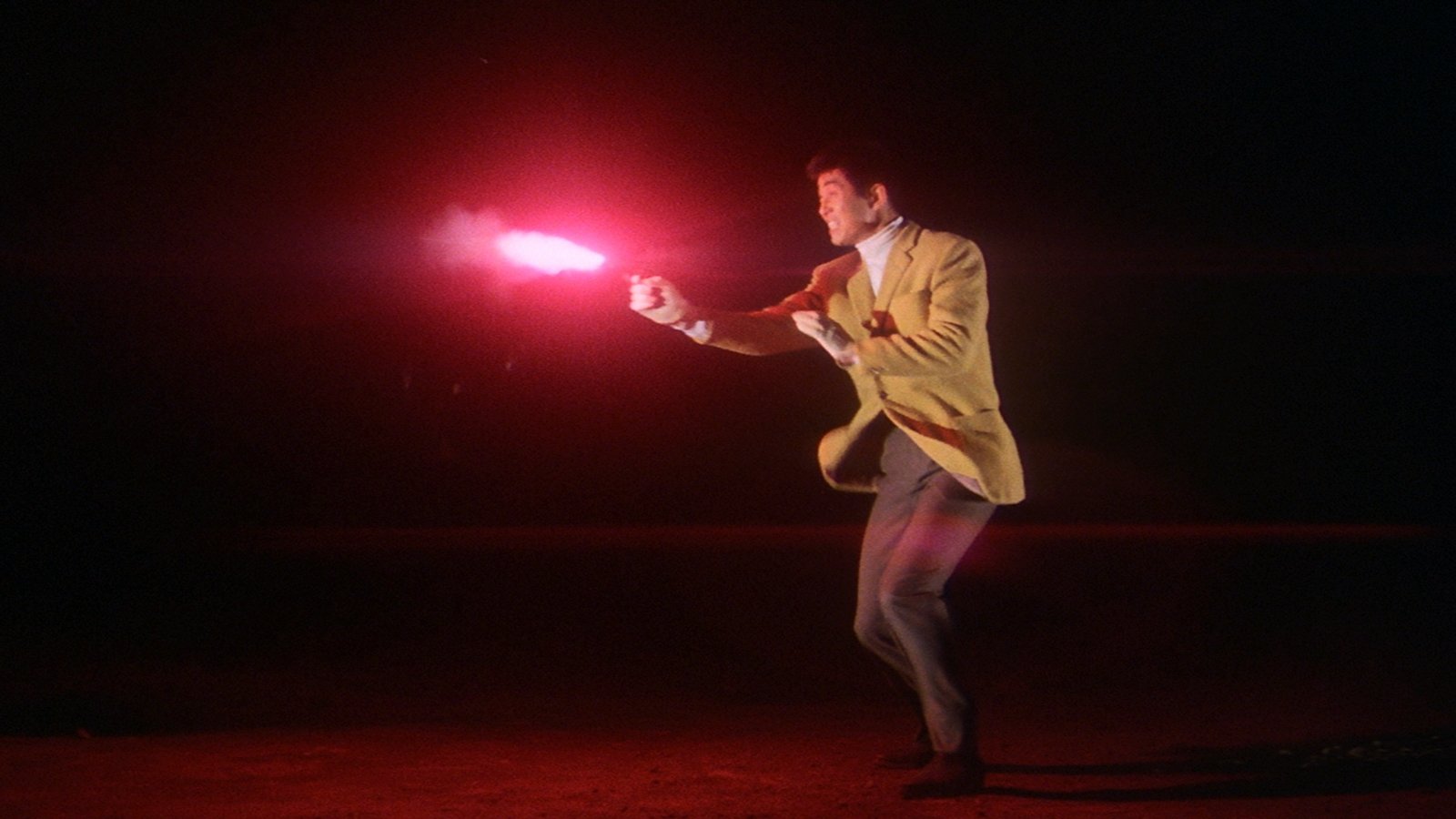

The minute, and obvious, details of Tokyo Drifter’s mise en scéne are what captures Suzuki’s stance on the corruption that stems from organized crime, as well as the silly proposition that Yakuza’s are invincible because of their consistently rugged portrayal in mass media. Suzuki makes a mockery of this facade by employing surrealism by way of implementing stagey and stylistic devices. Tokyo Drifter pays homage to America’s Western genre in terms of Japanese setting by absurdly choreographing extensive fight sequences where most involved are left without a scratch. To reinforce the proposal that Yakuzas are not untouchable, the only victims that suffer visible wounds are those who are enemies to Tetsuya, while Tetsuya is virtually unscathed for most of the film, excluding a gunshot wound that he seemingly is physically unaffected by.

Suzuki also emphasizes the need for criminals of the Yakuzas’ stature to constantly boast their sense of elitism. Otsuka dons a black coat that layers upon a red jacket, which is only revealed during his first physical altercation of the film. Otsuka finally shows his true colors, just as a male peacock would flash their vibrant feathers in order to seem more enticing. More than this, Suzuki also finds humor in other common tropes such as the damsel in distress, as Tetsuya ignores every single romantic advance made on him.

Tokyo Drifter’s cinematography and soundtrack complement its extravagant production as well. Constant pans and zooms alter the focus of each scene multiple times, never letting the audience’s eyes rest for a moment, while Tetsuya and Chiharu occasionally break out into song as a comical replacement for narrative exposition. The film also uses montages to make the vast environment of Japan seem much more compact and restricted to only what the mise en scéne allows us to see.

Tokyo Drifter is a film that constantly tries to look cool, but avoids presenting itself as pretentious through direct examples of self-awareness that limits tension from becoming full of itself in all its seriousness. The rapidly spontaneous pace of each scene’s composition, as well as the incessant stylization can become overwhelming, but it’s also easy to appreciate it as Suzuki’s ode to cinematic lore. Ridiculous at times, intense at others, Tokyo Drifter certainly contains every element of an engaging action film without the exacting cohesion of a director with strict intentions.