The other shoe has dropped for hypebeasts

The Box Logo design is a Supreme staple. (Photo courtesy SGB Media)

It was a Thursday in 2017, I had Geometry at my middle school that morning. I had a quiz, as I did every class, but the only numbers I had been studying were the several on the front and back of my parents’ credit card. I had a paper in front of me with questions that should have been my ultimate focus and goal for class that day, but there was a more pressing objective ahead of me. It was 10:30 A.M., my heart began to beat faster as each minute passed, but I had prepared for this moment. I felt like I was re-, no, I knew I was ready for what was in store for me. The clock ticked to 10:58, my nerves began to become exacerbated by the fact that a classmate was gone with the hall-pass for the bathroom; only one student could go at a time and I needed to get to my mark at 11. A minute passed, I raced to my peer to swipe the hall-pass as I asked my teacher if I may use the restroom, I may. There were 20 seconds until 11, I whipped out my phone and had all the necessary credentials prepared. It was time; I refreshed my page, entered my information, but I was out of luck. I returned to the classroom defeated, but I felt a vibration coming from my pocket. It was a notification, an email notification. The tides had turned, it was confirmed; I was the proud new owner of Supreme’s new collaboration with Nike: the Nike Air More Uptempo in Supreme’s iconic red and white color-way.

All of this may seem anticlimactic and trivial to those who were not in touch with the hypebeast renaissance of the mid-2010s, but I was tapped in. This was an era of materialistic gluttony and supreme indulgence (pun intended) that was guided by brand identification and luxurious flamboyance. Absurd items like the Supreme Brick retailed for $30, but was valued 5 times over on the resale market. Supreme and Palace’s weekly drops on Thursday and Friday, respectively, at 11 A.M. were not just fleeting moments, they were special occasions. Instagram and Twitter feeds were flooded by insider accounts that had previewed the items for each week and showcased how the most sought-after items would sell out in mere seconds. I had gotten into the game of reselling for love, but that love turned into greed and a lack of understanding of what gives life intrinsic value because of the excitement of the consumer-culture that I had bought so dearly into. What was once a movement that had people camping outside of Supreme’s brick-and-mortar stores for the pure bliss of buying a screen-printed t-shirt became an oversaturated market of copycats, lazy collaborations and ultimately sell-outs.

Rare sneakers and apparel could disappear from shelves and online stores in an instant, but you would never see their buyers donning the merchandise in public for the purpose of benefiting from being a professional capitalist. I was guilty of this myself; I began collecting sneakers and hyped streetwear pieces out of passion and a pure affinity for the zeitgeist it occupied, but the exorbitant opportunities to profit were undeniable and unavoidable. I bought products like the Supreme Money Gun, a Supreme Inflatable Blimp and I would have bought the aforementioned brick as well, but I didn’t give the brand my money quickly enough. Even though I had no intention of keeping any of these items, there was an exciting innocence to the hypebeast culture. It was like becoming a member of an exclusive club, where those who could get “drops” (eventful brand releases) for retail value were seen as the kings of the kingdom. Brands began to realize this though, and as their guerrilla marketing techniques became either more commercialized or skeletal, the fans began to disperse.

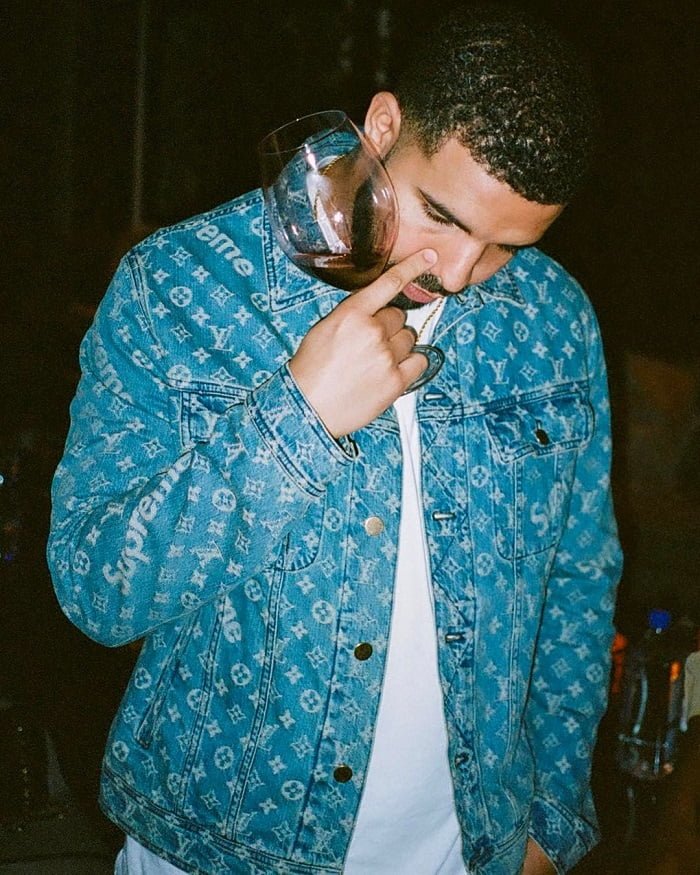

Drake wearing a denim jacket from the Supreme x Louis Vuitton collaboration. (Photo courtesy of KLEKT)

The watershed moment that ended the prime hypebeast era was Supreme’s collaboration with Louis Vuitton. Supreme was known for its rejection of the mainstream; it had previously even used an imitation of the iconic Louis Vuitton monogram for a prior release that had them served with a cease-and-desist notice from the legendary fashion house. Regardless, the unlikely pairing came to fruition in 2017. What was produced was some of the most lackluster designs in Supreme’s history, whether it was throwing the monogram on a hoodie colored in with Supreme’s signature red (which retailed for $935) or a bunch of leathered goods that would have never sold without Supreme’s stamp of approval. Following this was a steady decline in consumer engagement that was spearheaded by its main demographic, teenagers and young adults, maturing out of an age where graphic hoodies and expensive sneakers were all the rage. Louis Vuitton had seen enough to grasp Supreme’s influence on pop culture after the collaboration; the high-fashion label’s private equity firm, The Carlyle Group, bought a 50% stake of Supreme, valuing it at about $1 billion. A far cry from the days of bootlegged designs and cease-and-desist letters that provoked the traction the skating brand had begun to receive in their earlier years.

After The Carlyle Group officially thrusted Supreme into the mainstream, other hypebeast-adjacent brands like Anti Social Social Club (ASSC) and Bape began to lose the creative leeway that was once provided by their respective fans. ASSC particularly embodied how streetwear lost its competitive edge in the fashion industry, as buyers became reluctant to continue supporting a brand that took months to ship their up-charged products, even though they were used to be printed on the lowest industry standard of blank apparel, Gildan. Then there were brands like Bape and Palace who still maintain a prominent space in the streetwear realm of fashion, but often rely on high-profile collaborations when they aim to completely rid themselves of inventory rather than original designs.

It didn’t help that while the streetwear market was imploding, high-fashion brands like Vetements and Balenciaga began to depict the hypebeast trends as caricatures, further dispelling the illusion of rationality that came with buying something like a branded brick. Vetements executed comedic collaborations spoofing streetwear, such as their efforts with the mailing service DHL, or Balenciaga’s collaboration with the extremely popular video game Fortnite that seemed to try to tap into the same youthful base that made brands like Supreme so successful. These were shallow attempts at replicating a crucial juncture in fashion though, and were often received as such.

Hypebeast-mania temporarily returned to prominence during the COVID-19 lockdown, when Netflix’s Last Dance docuseries about NBA legend Michael Jordan seemed to inject new exuberance into the reselling market, albeit specifically for Air Jordan sneakers. Different models of classic Air Jordans saw skyrocketing prices, and have seemed to sustain these evaluative levels, but the actual quantity of sales has not stayed consistent as both economic struggles during the pandemic and further time removed from the series’ release led to a gradual decline in momentum.

Looking at products like the legendary Supreme Box Logo t-shirts and sweatshirts resell at prices that pale in comparison to years prior is both a sore sight and one that should be welcomed though. Although the excitement of the years where weekley releases had a global scope of attention may have dissipated, those who are true fans of the brands have more accessibility to the labels they love for a fraction of the prices that once dictated the market. It is yet to be seen if the hypebeast archetype will reappear in our current times, but those who remember its cultural prestige will certainly reflect on the days where brand identity united a legion of followers with a common goal: acquiring more merchandise.